“Create a python script to count the number of r characters are present in the string strawberry.”

The number of 'r' characters in 'strawberry' is: 2

/ˈbɑːltəkʊteɪ/. Knows some chemistry and piping stuff. TeXmacs user.

Website: reboil.com

Mastodon: baltakatei@twit.social

“Create a python script to count the number of r characters are present in the string strawberry.”

The number of 'r' characters in 'strawberry' is: 2

Based on my cheatsheet, GNU Coreutils, sed, awk, ImageMagick, exiftool, jdupes, rsync, jq, par2, parallel, tar and xz utils are examples of commands that I frequently use but whose developers I don’t believe receive any significant cashflow despite the huge benefit they provide to software developers. The last one was basically taken over in by a nation-state hacking team until the subtle backdoor for OpenSSH was found in 2024-03 by some Microsoft guy not doing his assigned job.

In fact, electric vehicles have been common once before. In the early years of the twentieth century, there were three fundamentally different automobile technologies battling for supremacy, and electric cars held their own against competition from steam-and gasoline-powered alternatives, as they are mechanically much simpler and more reliable, as well as quiet and smokeless. In Chicago they even dominated the automobile market. At the peak of production of electric vehicles in 1912, 30,000 glided silently along the streets of the USA, and another 4,000 throughout Europe; in 1918 a fifth of Berlin’s motor taxis were electric.

The drawback of electric cars with their own onboard batteries (rather than trains or trolleys taking a continuous feed from a power line over the track) is that even a large, heavy set cannot store a great deal of energy, and once depleted the battery takes a long time to recharge. The maximum range of these early electric vehicles was around a hundred miles, (Ironically, about 100 miles is still the maximum range for modern electric cars: technological improvements in battery storage and electric motors have been perfectly offset by an increase in car size and weight, and drivers of electric vehicles suffer from “charge anxiety.”) but this is farther than a horse and in an urban setting is more than adequate. The solution is, rather than waiting for the battery to be recharged, you can simply pull into a station for a quick battery pack exchange: Manhattan successfully operated a fleet of electric cabs in 1900, with a central station that rapidly swapped depleted batteries for a fresh tray.

From The Knowledge (2014) by Lewis Dartnell, chapter 9 “Transport”. Cited works for the history of electric cars are:

So, you’re telling me my plan to measure atmospheric oxygen isotope trends over geologic time by grinding up sharks is bust?

We could probably spin it around and give a tiny tax break for those who vote.

Now you’re talking!

Make tax refunds and all tax write-offs contingent on proving you voted. >:D

I agree, but Earth’s solarpunk phase doesn’t start for another few millennia. We’re still in the era where factory farms still exist.

Reminds me of a quote from Galactic North (2006) green marking the start of a galaxy-wide disaster (terraforming bots making the galaxy terrifically habitable).

It was impossible for stars to shine green, any more than an ingot of metal could become greenhot if it was raised to a certain temperature. Instead, something was veiling them – staining their light, like coloured glass. Whatever it was stole energy from the stellar spectra at the frequencies of chlorophyll. Stars were shining through curtains of vegetation, like lanterns in a forest. The greenfly machines were turning the Galaxy into a jungle.

Wow, satellite photography sure has improved since 1965.

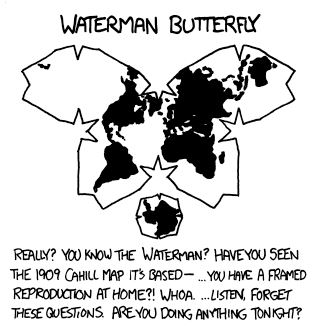

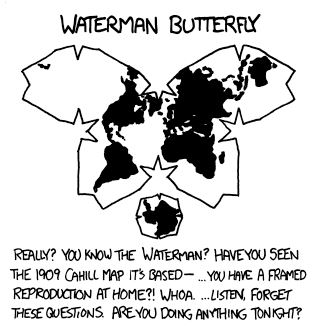

Unfortunately, I cannot find a non-rasterized digital version even though the original clearly was a digitally typeset document.

So, Fuwamoco are Italian or Bangladeshi?

Maybe they’re using a point end shoot?

As someone raised in the area and grew up Mormon, my understanding is that ham and cheese potato casserole is a typical dish served at funerals in Utah because its easy to prepare and therefore less hassle for grieving women at funerals who often were tasked with not only funeral-specific tasks but the food prep as well. This 2023 article from Deseret News (a pro-Mormon news organization) gives an introductory history.

After reading The Age of Em (2016) by Robin Hanson, I wish there were stories about races that went the other way, lifespan-wise: extremely small people who lived only 1 year, even smaller people who lived only 1 month, some very extremely small but very powerful ones that lived only a day, etc. The idea is that artificial people (emulated people, or Ems) could have subjectively similar characteristics and experiences to the larger physical entities (e.g. humans, but perhaps even dwarves, elves, and etc., since theyʼre just emulated minds), but their artificial emulated substrate allows their minds to develop and age orders of magnitude faster; they also could solve certain problems orders of magnitude faster but practical limitations on delays between thought and physical interactions (your mind would waste away if you had to wait a whole subjective hour between each physical step during a walk with a standard 1.5 meter body) require their bodies to be very small.

Call them speedlings, or some variant of sprite, but I think its an interesting world-building concept.