9ft of snow?! I only experienced such deep snow in an urban setting while living in Connecticut for a year. I spent a few years in Oregon but the snow in the area never got so deep while I was there. When I was in the US I was not yet able to identify many fungi as I was mainly obsessed with animals (especially salamanders) back then, so unfortunately I did not really appreciate the diversity of fungi there. Although once in Oregon I did attempt to dye some socks using a wolf lichen (Letharia vulpina) and a pressure cooker. That did not end well.

Salamander

- 52 Posts

- 159 Comments

I see. So it is not necessarily that their mycelium are better at surviving the freezing temperatures, but rather that either they fruit quicker once conditions are acceptable or that their fruiting bodies are more cold tolerant. Thanks, it’s interesting.

Cool! I just read their wiki page and it says

A snowbank fungus, it is most common at higher elevations after snowmelt in the spring.

Snowbank fungus is a new term for me. Not sure yet what makes a fungus thrive through snow. Maybe they have anti-freeze proteins?

Does your area get a lot of snow?

4·27 days ago

4·27 days agoWow, those spores are so bumpy, they are very interesting! Thanks for sharing :D

Thanks for the idea! That looks very nice, I like how the collection is organized in those storage containers. They look very well preserved so far so your well water + sun protocol seems to be working well. Perhaps I will too start a lichen collection!

Always happy to talk about molecules interacting with light! 😄

This is an aspect of lichen I hadn’t really put much thought into before now.

I have some background is in studying how light interacts with molecules, so I probably put more thought and emphasis on these things than average.

Its been in storage for a couple of months so I may try to re-hydrate it a bit before lighting it up during the night.

That’s cool! When keeping a collection, can you keep them alive for a long time dry?

Not sure how I managed to never hit this species with UV. I would describe the colour as a bright, hot, lipstick pink. I am unsure if this lichen is actually fluorescing or if something else to do with how the pigments show up under UV light - maybe @Sal@mander.xyz would know. Picture doesn’t quite do it justice.

You are pointing a UV lamp at it which probably sends out 365 nm or 395 nm photons. The lichen is shooting back photons with a broad range of wavelengths, and a lot of ~600 - 750 nm ones (red). So, the UV photons had to be “captured” by some molecular system, the system dissipated some energy, and then re-radiated some of these longer-wavelength photons.

The general term that covers the many different possibilities is “photoluminescence”. In this case we can say for sure that the lichen exhibits “UV-induced photoluminescence”, because it is re-emitting lower energy (longer-wavelength) photons. It is common to make the connection “photoluminescence” = “fluorescence”, but technically fluorescence makes specific claims about how the light is re-emitted (singlet -> singlet emission), and it is not the only luminescence process. Other examples of luminescence are phosphorescence from a triplet state and luminescence via charge-recombination. So, to call it “fluorescence” in the strict sense we need know what the exact pathway is.

That said, when it comes to biological pigments fluorescence is generally the most common pathway. Triplets that live long enough to produce light are generally undesirable as they can react indiscriminately with molecules inside of the cell as well as produce reactive oxygen species, and good phosphorescent materials often combine metals and heavy atoms that are not as abundant in living tissue.

So, knowing nothing else, and seeing that red light comes out when you shine UV/blue light on a lichen, it is generally fair to call it “fluorescence”.

Now, if we discuss this specific lichen… I have looked it up and it does get interesting! Do you have it with you? I suspect that its fluorescence might be different during the day than during the night.

I can find online two significant fluorescent components: parietin, which produces the fluorescent yellow pigment, and Chlorophyll a/b, which produces red fluorescence. There is an interesting paper exploring the idea that one functional purpose of parietin’s fluorescence is that it can transfer energy to the algae to boost their photosynthesis. Their conclusions in the paper is that the idea is not supported by the evidence, so, a “negative result”. It is a fun example of the type of research that is performed in photobiology and also an example to show that even negative results can be interesting enough to be published!

As for the difference between day and night - if what you see is a combination of the fluorescence of parietin and chlorophyll, then the color might change with the day/night cycle. Photosynthetic organisms regulate the flow of excess photon energy towards a safe non-radiative dissipation pathway in response to light. This is called the non-photochemical quenching pathway, and during the day this pathway tends to be active. During the night there is little light, and so this protective pathway shuts-off. This allows more of the absorbed photon energy to flow into the radiative fluorescence pathway, increasing the red fluorescence. You can actually see this easily with plants - you can dark adapt a leaf and then compare its fluorescence with that of a leaf that is being exposed to a bright light. The dark-adapted one will usually show significantly more red fluorescence.

This time you did ask, so I won’t apologize for my essay 😆 But I am a bit sorry I didn’t have the time to make it shorter.

3·1 month ago

3·1 month agoBeautiful! Thanks for sharing!

When I saw it, I thought “this looks like it must be fluorescent under UV!”. So, I looked it up, and found out that it probably isn’t fluorescent (but if you have a UV flashlight to test, I am quite curious to know).

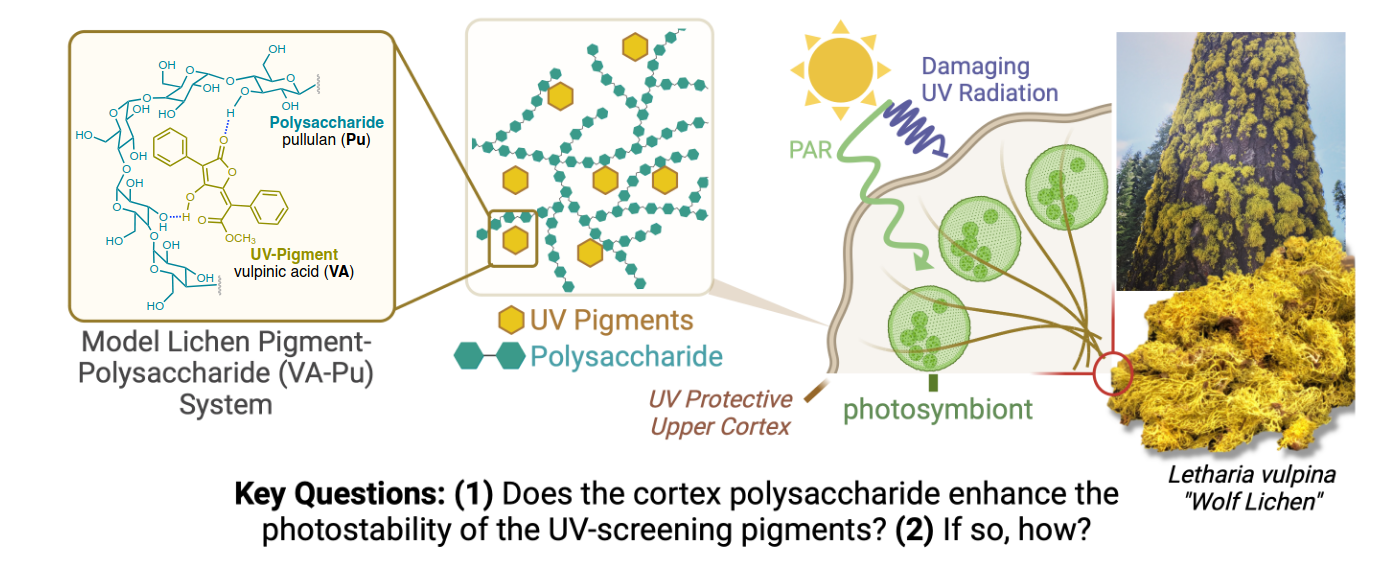

From what I can find, the yellowish green color comes from the molecule vulpinic acid. Especially interesting is that this molecule is prone to breaking down in the presence of light (terrible quality for a pigment), but a recent paper suggests that inside of the lichen the molecule sticks to polysaccharide chains in a way that dampens the molecule’s photogradation pathway. The pigment can still absorb UV light but rather than dissipating the energy in a destructive process the polysaccharide holds the molecule in place and dampens the molecule’s response by quickly dissipate the energy. Here is the open-access paper, and diagram below.

I also found that the name Vulpicida, Letharia vulpina, and Vulpinic acid come from folk tales about these lichens being used to poison foxes (vulpes = fox) and wolves. Not sure if it is true…

Apologize for the information dump, but I saw the bright colors and just had to look into its photophysics 😂

6·2 months ago

6·2 months agoI am privacy conscious and care about privacy even though I don’t care too much about my own personal privacy just for privacy’s sake.

Privacy advocacy runs deeper than just protecting your own data. Convincing someone to care about “their privacy” is more straightforward when they face a real threat. For example, a journalist in Mexico writing about a politician linked to organized crime has every reason to avoid being easily tracked. That person is not going to post their location on Facebook.

But most people aren’t under direct threat. If you read my texts, you’ll find casual conversations with family and dinner plans. I’m not afraid of someone showing up at my door, so I’m fine sharing my address to get a package delivered. Getting ads is a minor annoyance.

Still, I care about privacy. Not necessarily mine, but privacy as a principle. I care about what surveillance capitalism does to society. Even if my personal threat model is easy, I want tools and systems to exist for people with harder ones. Privacy is part of the kind of world I think we should live in, and its erosion usually points to larger structural problems.

So back to the question. It’s easier to convince someone to care about privacy if they feel directly threatened. But if they don’t, you need something else to make them give up convenience in the name of privacy. That something is ideology. You’re asking how to shift someone’s ideological framework. That’s hard, and not something you can do for them. You can recommend good material, share your reasoning, explain what led you to care. But they have to engage with the ideas themselves. Like with exercise, you can’t build someone’s muscles for them. You can’t implant the ideology, but you can create the conditions for it to take root.

3·2 months ago

3·2 months agoThe book arrived :D Exciting!

I do want to try the single-spore isolation technique at some point.

5·2 months ago

5·2 months agoThat’s a good idea, I will give it a try. I also want to learn more about how to apply dyes to see the different structures.

I have been looking for good books on fungi and lichen. I have ordered that book, should arrive this week! Thank you for the recommendation

Absolutely stunning!

7·2 months ago

7·2 months agoThanks! Today I collected a tiny piece of the lichen and set up a new experiment to grow the algae!

The lichen organism consists of a combination of different species combining into one — a form of symbiosis. Generally, the lichen consists of at least one species of fungus, known as the mycobiont, and at least one photosynthetic alga or a cyanobacterium as a symbiotic partner, known as the photobiont. It is possible to have more complicated mixtures, not necessarily only two.

The fungus grows on a surface and then undergoes a process of lichenization. In this process, it can capture its companion from the environment (it may arrive via arthropod activity, such as through saliva or feces), and then produces structures within which they reside, as shown in the diagram below.

Source: New PhytologistThis relationship is beneficial to both organisms because the lichen can “mine” nutrients like phosphorus and also provide protection, while the photobiont can make use of light to produce sugars for the fungus.

It is difficult to cultivate these by picking one from the wild (except perhaps if you bring the lichen along with the surface it lives on), because this state of symbiosis is strongly adapted to the surface the lichen grows on and it has gone through a developmental history that is not easy to replicate from a small fragment.

One way to grow a few specific species of lichen is through a process of re-synthesis. This process consists of first growing the fungus and the algae separately, and then re-combining them to create the lichen.

Source: BMC GenomicsI still have not gotten to the point… but I have read about it and I think I now know how to do it. I need to make an agar plate like the ones I showed in the post that contains nutrients, but then place a thin regenerated cellulose or cellophane membrane on top of it that allows nutrients to flow slowly, but that the fungus is unable to penetrate, forcing it to only grow in a plane. After it has grown for a couple of days, the algae can be added in a specific ratio for the fungus to capture and become a lichen.

Hope this explanation helps clarify!

Here is also a very nice video on lichens: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0GOgiJlHkcY

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoWow, the acoustic spectrum feature is amazing! I have been coming back to it a few times over the last couple days to try to understand what I am seeing and listening to here. In the log plot I can see these lines of power increase that happen usually between 10:00 - 15:00 and often peak around 12:00. May 1 around 5 pm the bees appear to have been buzzing louder than usual. Is this the swarming sound?

It is really really cool, and I love that you have been able to apply ancient magic on this!

I myself have been playing recently with a CO2, temperature, and humidity sensor from Sensirion (SCD41, costs about $13 from China on a breakout board and talks I2C). I use this one for controlling a mushroom chamber, and I can see the CO2 released by the mushroom (or human activity nearby). It may be interesting for you as well, as I can imagine swarming might be associated with a CO2 spike.

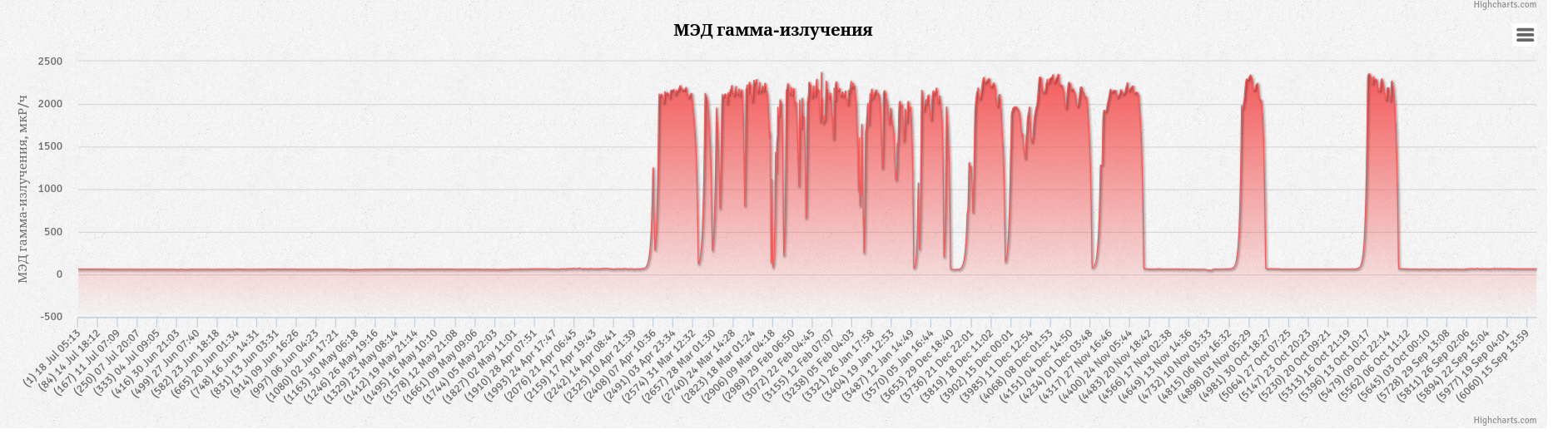

The radiation levels are also very cool! I have a few gamma spectrometers and have tracked radiation for a bit, but I got a bit bored of measuring background radiation in my apartment in Amsterdam. But I do want to set up one again, just in case it catches some interesting spike.

It is difficult to keep track of the year because the year is not listed along the X-axis. On page 7 and 8 of Припять I see spikes of up to ~2300 MR/hr, are these true, or measurement glitches? If true, do you know what happened?

Very cool stuff, thanks for sharing!

6·2 months ago

6·2 months agoVery cool! Nice work :D

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoThanks a lot for sharing! It has been nice thinking about this topic again.

When I wrote my response I was hyper-focused on the concept of “antenna-like” resonances due to the wavelength of the radiation, so it was interesting to read about the 500 Hz resonances that I assume are due to natural frequencies of tiny hairs or other oscillators in bees. I did not even consider these.

I have in the past heard about some micro-wave and also IR-assisted chemistry. It does make some intuitive sense that the excitation of particular modes that displace molecules or groups of molecules along a reaction coordinate might help speed up a specific reaction pathway, but I remember a few years ago that the data was not there to support that. I believe a professor at my university was doing some experiments in which the reactants are placed within a cavity that is resonant with such a mode in an attempt to increase reaction rates via some cavity enhancement. From what I can see they have not published on this topic yet, but it seems to be related to this concept: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/154/19/191103/565904

I am very curious about your LoRa bee sensors. What kind of sensors are you using?

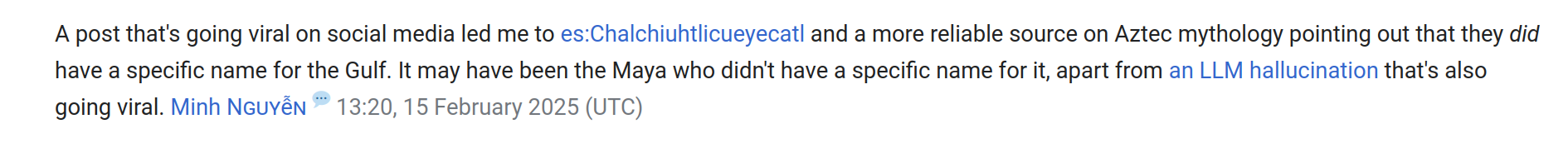

I think the difference in time is too big. Also, in the talk page’s archive it is stated that the wikipedia was updated because of this meme, and not the other way around. This is from the talk page:

Looking through the archived history of the talk page, I can confirm that the claim on the wiki page is derived from the viral post, and not the other way around: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Gulf_of_Mexico/Archive_3#Chalchiuhtlicueyecatl

How did I miss that?!

My timeline is incorrect then. Since the post from sassymetischick.bsky predates the wiki edit, it is more likely that the wiki edit was made in response to this meme, and not the other way around. This pretty invalidates what I said above…

I still can’t find any evidence of this being an actual trend, but I no longer have a good guess about the origin.

Would love to… When I was in Oregon this lichen was super abundant. At the moment I am living in Amsterdam (Netherlands), and I see mostly Xanthoria, Evernia, Rhizocarpon, and a few other lichen species that grow on city trees, but they are very small and spotty, nothing compared to the wolf lichen in Oregon. I do miss the Oregon forests with the old growth sequoia redwood trees and all that lichen.